Sunday, May 14, 2006  The next village we visited was Tomu. They have just started a women's sewing group there to make and sell clothes. The start up money is coming out of the BP compensation fund, and then the field staff from the BP community development unit will help them get it up and running (training etc). Some of the sewing machines were Singer - I am sure not Clydebank originals but made me smile all the same. This girl is not actually in the sewing group (no child labour ha )but she just wanted to have her picture taken. This other wee one had her new dress on but was really grumpy to have her picture taken ...  Me and Salim (the local nurse) were cooking lunch here, in the kitchen of the clinic. Bit fat juicy prawns 2 quid for a kilo ... As usual the fact that I can cook (because of course at home in my castle usually all my maids cook for me) was met with laughter and surprise. I was praying I didn't f- it up to prove them all right but I managed to pull it off I reckon. Me and Salim (the local nurse) were cooking lunch here, in the kitchen of the clinic. Bit fat juicy prawns 2 quid for a kilo ... As usual the fact that I can cook (because of course at home in my castle usually all my maids cook for me) was met with laughter and surprise. I was praying I didn't f- it up to prove them all right but I managed to pull it off I reckon.Prawn fishing is the main source of income here, and a very lucrative business by Indonesian standards - the fishermen get 20-100kg a day and sell for Rp25,000/kg (just under 2 quid). Even after taking off the cost of fuel and ice, it is still possible to make a pretty reasonable income. That said some days are bad days, and most of the men only go out 3 days a week ... It's strange though - the standard of living is still so basic, but actually if you work it out, they can make a lot more from the prawns than if they go to work on the plant (and even that is a pretty decent local salary too).  The water was high when we wanted to go home, so the speedboat was able to reach the jetty (left) - apparently sometimes it can't get in as the water is too low, so you have to walk through the mud for a couple of kms to reach it. Needless to say I was quite happy to avoid that scenario ... The water was high when we wanted to go home, so the speedboat was able to reach the jetty (left) - apparently sometimes it can't get in as the water is too low, so you have to walk through the mud for a couple of kms to reach it. Needless to say I was quite happy to avoid that scenario ...

This is one of the dukun paraji, or traditional birth attendants I met in Taroy. Part of the program here has been training women like this in safer delivery practice and providing sterile dukun kits. This was at one time the backbone of public health programs to reduce maternal mortality in poorer countries, but in recent years, research has shown that it doesn't seem to reduce the death rate. However, the fact of the matter is that in many of these villages there is NOONE else at all to help women give birth, so trying to reduce harmful practices, and protect good ones, is a just a little common sense. This is one of the dukun paraji, or traditional birth attendants I met in Taroy. Part of the program here has been training women like this in safer delivery practice and providing sterile dukun kits. This was at one time the backbone of public health programs to reduce maternal mortality in poorer countries, but in recent years, research has shown that it doesn't seem to reduce the death rate. However, the fact of the matter is that in many of these villages there is NOONE else at all to help women give birth, so trying to reduce harmful practices, and protect good ones, is a just a little common sense. Another contradiction - credit for your mobile phone is being sold here! In a place where most families do not even have toilets, there is now Telkomsel coverage - thanks to BPs plant opening and a new antenna being erected.  This is the view from the jetty in Taroy, one of the so called "in-directly affected" villages in the project area. They do not have to be resettled, but their fishing grounds will be affected by the development, and as such qualify for compensation. This is the view from the jetty in Taroy, one of the so called "in-directly affected" villages in the project area. They do not have to be resettled, but their fishing grounds will be affected by the development, and as such qualify for compensation.In fact, although the amount of money allocated to these villages is much smaller, it is still a very significant amount of money. What's more, it doesn't go through the government at all so the classic Indonesian corruption potential is bypassed. The way it works is that BP's community development team facilitate a planning process in the village. When a budget has been allocated by the community, up to the total value of that years compensation, then BP release the funds directly to the village, for each planned activity. In this village, part of the money last year was used to build walk ways (see left) - previously the whole village was just a big mud bath apparently ...  In some ways I think this is a far better way for BP to provide its compensation. There was a completely different attitude in this village compared to the one that has been resettled and everything rebuilt. A real sense of people wanting to help in the process, not just sit and wait for BP to provide everything. They have so far built a school and a clinic and put boardwalks down throughout the village. This is the Village Secretary (left) and another guy, who I met when I first got off the boat. They were very keen to have their picture taken, but in true Indonesian style, immediately stopped smiling as soon as the lens pointed their way. In some ways I think this is a far better way for BP to provide its compensation. There was a completely different attitude in this village compared to the one that has been resettled and everything rebuilt. A real sense of people wanting to help in the process, not just sit and wait for BP to provide everything. They have so far built a school and a clinic and put boardwalks down throughout the village. This is the Village Secretary (left) and another guy, who I met when I first got off the boat. They were very keen to have their picture taken, but in true Indonesian style, immediately stopped smiling as soon as the lens pointed their way.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

The photos below show the kind of view that confronted me as we went up the river to the village (all transport is by boat here). The picture on the right is of a gathering in the house of a baby that died yesterday, only one day old. It reminds me that despite the shiny new houses, the problems associated with poverty are still very apparent. The infant and child death rate here is very high - much higher than elsewhere in Indonesia. In Saengga, a village of only 100 hundred families or so, two children have died in the last week. I saw the father of one of them sitting outside his brand new house, beside the grave of his 1.5 year old - they had buried her just outside. He had put cans of coke and fanta on the grave for her to drink. It was so sad. It appears that there is an almost total failure of the health system here - correct diagnosis and treatment is a rarity, and the referral system (to more expert help and facilities) is ad hoc at best.

These guys are taking empty cardboard packing boxes and packing material for fragile goods over to the village, ready for the big move next week. BP seem to have thought of everything - even down to the packing! I had a wry smile on my face though - each family gets 15 boxes or so; I doubt very much they have enough stuff to fill more than 4 or 5 ... These guys are taking empty cardboard packing boxes and packing material for fragile goods over to the village, ready for the big move next week. BP seem to have thought of everything - even down to the packing! I had a wry smile on my face though - each family gets 15 boxes or so; I doubt very much they have enough stuff to fill more than 4 or 5 ...

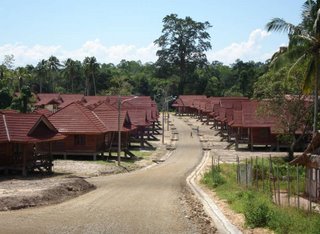

Today I went to the resettled villages. In a nutshell, BP is building an onshore processing plant for gas piped from its offshore operation in Tangguh. In order to put the processing plant where it wants, BP had to relocate an entire village, called Tanah Merah. As compensation for this, BP have built a new village - one house per family, including kitchen, bathroom and toilet, running water and electricity. As part of the deal, BP have also built schools, sports facilities, churches, mosques, health facilities etc - in short its very complete. The houses are beautifully done, and I am pretty sure none of those families ever imagined they would have a house like this in their lives. Because the new village (Tanah Merah Baru) is sited on the land belonging to another village (Saengga), that village has also been compensated similarly, one house per family. In Tanah Merah Baru, families are already living in their new houses, but in Saengga the moving date is next week. This post (below left) shows Sisilia's (one of the health project's local workers) old house, where she lives with her husband and 5 children. Next Friday she will move to her new house (below right). She and her husband are so over the moon it was lovely.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006Tuesday, May 09, 2006 This is the surprising illegal italian restaurant/bar on the roof of a house in Aceh. Sharia law is applied in Aceh, so selling alcohol strictly forbidden. You ring a door bell to get in here and they peer out at you to check you are not the police ... Had a great night - food, wine and music under the stars - totally bizarre. This is the surprising illegal italian restaurant/bar on the roof of a house in Aceh. Sharia law is applied in Aceh, so selling alcohol strictly forbidden. You ring a door bell to get in here and they peer out at you to check you are not the police ... Had a great night - food, wine and music under the stars - totally bizarre.

Sunday, May 07, 2006 This was previously an offshore power station, providing electricity for part of the city. It is now slap bang in the middle of a residential area several km inland, coming to rest right on top of some houses (and squashing them flat). It does give you a sense of the height of the water – as the houses around it are barely damaged it must have gone above them, and the ship itself must draw at least a couple of metres. I am opening this blog as it will be easier to share photos, not really for blogging but as it’s a Sunday and I have been back in Indonesia over a month already, I will post some news. I was told that about 50% of my time would be spent visiting projects, and 50% in the Jakarta office. At the moment it is more like 95% and 5%, but this suits me, as Jakarta is great in small doses … About PCI: Project Concern International (PCI) have been working in Indonesia for many years, and at intervals have worked pretty much all over the country. Currently their projects are as follows: Joint Livelihoods and Health Project in Aceh – this followed on from the relief work PCI did during the emergency period after the tsunami. The livelihoods part is funded by UNDP, and the Health part by AmeriCares (American private funding). The livelihoods component has been running for a couple of months already, but the health part is just starting now. In Pandeglang, SW Java, they have a Child Health project funded by USAID. This has been running for 2.5 years and by all accounts is a successful and well-respected project. In Papua there are 2 projects already running (one HIV one, based in Nabire (lowlands) and Paniai (Highlands) that has just started, and one community health one in Bintuni Bay that forms part of BP’s social responsibility commitment in the area), and then in the very near future there is likely to be a Maternal and Child Health project starting up in Nabire, to run alongside the HIV project, but that is still pending the final OK from funders. My job is essentially to advise the start up phase of the Aceh project and 2 new Papua projects, and also provide technical input into the BP project. I also have to make sure any learning from the project in Pandeglang gets transferred to the new projects. The only thing is that the staff here are really skilled with a lot of experience so when I first started I was like – what do they actually need ME for. But as the weeks have passed it has become clearer to me what I can offer so that’s great. Jakarta and around: So now ... what have I been up to the last few weeks … I got a kost (lodgings) in Jakarta, dangerously near the shopping Mecca of Senayan, which sucks me in at every opportunity (having spent so long in Ende I am still amazed there is a whole AISLE of body lotions to choose from in the supermarket and I can spend a lot of time in there). It is about 5-10 mins to the office on a bajaj (terrifying, black smoke producing motorised rickshaws, every single one of them on their last legs) or about 10-15 mins in a cab (because they get stuck in the traffic more). I have to say I prefer the craziness of the bajaj, even though my green rating must be seriously in the red. So last month I was in Jakarta for 5 days only. It is a massive city, constantly grid locked and as polluted as anything. That said there are definite charms that I can see – lots of interesting things to see just by watching people, thousands of tiny food stalls selling at all hours, great shopping (from cheap as hell market rummaging to air-con Prada), good nightlife and funnily enough, thanks to the pollution, some beautiful sunsets. Otherwise, I went to visit the Pandeglang project to help with training for the village health facilitators for a week, and then I had a week at a Training of Trainers course for Stepping Stones (which is an apparently very successful way of getting communities to talk about and understand HIV) (with a weekend in Bali in between, which was fun). Stepping Stones has been used a great deal in Africa and India, but it has yet to be tried in Indonesia. The course was to train our staff so we will be able to train field facilitators in Nabire and Paniai in Papua, and then they will work through the course with men and women in the villages. It was an interesting week. It has been a while since I have been a participant in a training course, as opposed to the trainer. It was also more of a self-analysis about your own attitudes/ behaviours (the kind of methodology it uses). I found it an incredibly emotional week actually. Aceh: The rest of the time since I arrived I have been based at the Banda Aceh office. It’s a strange place to describe, Banda Aceh. Firstly there are something like 150 international NGOs currently operating here, with about 2000 expat staff between them. This makes Banda Aceh the 3rd largest cluster of expats in Indonesia (after Jakarta and Bali). Associated with this, local inflation is standing at 30% at the moment, as shrewd locals see the opportunities of all these expats with dollar pay packets. Before the tsunami, Banda Aceh was an affluent city – the houses (in unaffected areas) are MASSIVE – not at all like I have seen elsewhere in Indonesia, except perhaps in certain parts of Jakarta. Its an interesting situation though, because it means NGOs in Banda Aceh are working with well educated, relatively wealthy (at least pre-tsunami) families which means the dynamic is totally different from other settings. In the villages of course it was not nearly so affluent, but still the people I have talked to are much better educated than their counterparts in Flores. Certainly for community health programs it makes the problems very different. Of course these are all first impressions and I may be way off the mark. The first time I came up here I felt decidedly uneasy about the whole situation and conscious that here I was just another NGO worker adding to the mess. It’s difficult to explain what I mean. A disaster on such a massive scale of course requires a huge relief effort – that I do not question. Thousands of people came out of the tsunami with their lives and NOTHING else. Even the clothes on their back were shredded. But now that at least in a few areas the immediate relief phase is over – people have been rehoused and sanitation has been restored. I am not sure whether the massive presence of NGOs is doing more harm than good. I can’t help wondering in the long term what this is doing to the social structure here, in terms of creating this real ‘hand-out’ atmosphere. I realise it’s a controversial viewpoint, but it has crossed my mind that it is possible that if all the agencies left, after essential relief work was completed (infrastructure, housing) there would be less of a mess than if they all stay. More on this another day - it's still a black thought floating around in my mind … The scale of the tsunami is truly unimaginable for me. More than one hundred and ten thousand people died here in one morning. How do you comprehend that? When you get into the directly affected area, its just mile after mile of ceramic floors where all the houses were. The main coastal road was destroyed – you can see funny little patches of it here and there. One of the villages where we work used to have a hill on its Western side. The water LEVELLED the hill. It is just not there anymore – there is a hole in the row of cliffs/mountains where it was. In that village I was speaking to the village head. He is about the same age as me, maybe a few years older. 75% of the population of his village was killed, most of them women and children– they used to have 26 under 5 years olds who attended the monthly clinic to be weighed – now they have only 5 or 6, including babies born after the tsunami. He has a new house now, but in the same spot as the old one and we were sitting outside it. I would say it’s about 250m back from the sea. He told me that previously you couldn’t see the sea from his house because there were so many palm trees (now there are only 1 or 2 dotted about). On the morning of the tsunami they were sitting outside and they did hear something strange but they thought it was a strong wind. It wasn’t until the water was coming through the trees in front of the house that they realised it was a wave, and then it was on top of them already so they had nowhere to run. Those trees that are still standing I would guess are 4-5m high at least, and the water was over the height of the trees. So he managed to take a breath twice while he was caught up in the water. I asked him if he was scared to go in the sea now, and he said at first he was but now it’s almost like a dream, like it didn’t happen. I feel a certain degree of arrogance in me coming here with so many others and daring to think that I can do anything useful. That said there is much good work happening here – just basic things like house building and boat building. For most people it is happening too slowly though, and there are many people still in camps. A recent scandal, whereby some unscrupulous builders swindled Oxfam and Save the Children out of thousands of pounds, building ‘houses’ straight into sand with no foundations. The engineering assessment says they all have to be knocked down and rebuilt, but the builders are laughing. It’s so corrupt here that they probably won’t be held accountable. Investigations into the corruption on this and other cases have found that almost all the companies receiving building contracts are owned by a handful of very wealthy people... Because of this recent case, all building contracts have been temporarily frozen while they are investigated – further delaying the house building for all those families waiting in the camps. See this website for more: http://www.antikorupsi.org/eng/ It makes me crazy though. Blood money. People getting very, very fat from uang mayet (“corpse money”). Totally shameless. If there is a devil then he has got to be waiting for people like that. |